My Saigoku Pilgrimage (2001-2006)

Introduction. I became interested in the Saigoku pilgrimage

(Saikoku Sanjusansho junrei) after reading the Tale of Genji in

2000. I was fascinated at the importance of pilgrimage to Heian-era

aristocrats, and to women like Murasaki Shikibu in particular. So the

pilgrimage for me started out as a kind of cultural investigation, to

find out why it had been and still was so important in the lives of the

Japanese.

Introduction. I became interested in the Saigoku pilgrimage

(Saikoku Sanjusansho junrei) after reading the Tale of Genji in

2000. I was fascinated at the importance of pilgrimage to Heian-era

aristocrats, and to women like Murasaki Shikibu in particular. So the

pilgrimage for me started out as a kind of cultural investigation, to

find out why it had been and still was so important in the lives of the

Japanese.

I picked up

The Traveler's Guide to Japanese Pilgrimages - the only

English-language guide to the Saigoku pilgrimage - and Gateway to

Japan, which is probably the best guide to the culture of ancient

Japan. I did the pilgrimage as a series of day-trips from Kyoto and I

didn't visit the temples in sequential order. In retrospect, it was a

mistake not to learn more about Japanese Buddhism and about Kannon in

particular, but more about that later.

Ishiyamadera (#13) April 2001. This

was my fifth short visit to Japan and the first in which I visited

places mentioned in the Tale of Genji. Not only does Ishiyamadera

feature in the Tale, but according to legend the author began writing

her famous novel there.

I took a train from Kyoto's Keihan-Sanjo station, changing at Hama-Otsu for Ishiyamadera

station at the end of the Sakamoto local line. From the station I walked for 10 minutes in

the rain beside Lake Biwa until I reached the temple gate. After buying my ticket and

getting a leaflet in Japanese, an old lady just inside the barrier handed me an English

leaflet. Climbing the steps to the right, the rain stopped and I came out on the temple's

gravel courtyard, stone lanterns and a pagoda on the opposite side and water dripping from

the lush, green foliage. The scene had a kind of magical quality about it.

I took a train from Kyoto's Keihan-Sanjo station, changing at Hama-Otsu for Ishiyamadera

station at the end of the Sakamoto local line. From the station I walked for 10 minutes in

the rain beside Lake Biwa until I reached the temple gate. After buying my ticket and

getting a leaflet in Japanese, an old lady just inside the barrier handed me an English

leaflet. Climbing the steps to the right, the rain stopped and I came out on the temple's

gravel courtyard, stone lanterns and a pagoda on the opposite side and water dripping from

the lush, green foliage. The scene had a kind of magical quality about it.

Inside the hondo the image on display is a Nyorin Kannon and this is one of the few

temples that have benches for visitors to sit and contemplate it. But the original clay

image is displayed only once every 33 years. The hondo also has a long

balcony overlooking a small valley. Beside the balcony is an image of

Binzuru that visitors rub in the hope of curing ailments. Binzuru (Skt.

Pindola) was one of the Buddha's disciples. His reputation for occult

powers such as flying is perhaps why his image is usually seen outside

or at the entrance of temple buildings.

Leaving the hondo, visitors turn left past the Genji Room - which has a

life-size image of Murasaki Shikibu - and climb up past the

belfry and tahoto to the moon-viewing pavilion. You can't go in the

pavilion but the cherry-blossom below is beautiful in April and the

temple is open late on the eve of the Harvest moon. A path leads up the

hill to the treasure house and a little way past it a small trail leads

up to a pavilion and a statue of Murasaki.

Leaving the hondo, visitors turn left past the Genji Room - which has a

life-size image of Murasaki Shikibu - and climb up past the

belfry and tahoto to the moon-viewing pavilion. You can't go in the

pavilion but the cherry-blossom below is beautiful in April and the

temple is open late on the eve of the Harvest moon. A path leads up the

hill to the treasure house and a little way past it a small trail leads

up to a pavilion and a statue of Murasaki.

The path winds back down to the small valley beneath the hondo and its

charming garden centred around a carp pool and waterfall. There is a

pavilion for viewing the pond and irises in May. In recent years the

temple has cut down trees to plant daffodils and created rock terraces

up on the hill, while building iris beds in the pond. The result is not

as natural as it once was.

I returned to Ishiyamadera in September 2001, bought a nokyocho

(pilgrim's book) from the temple office and so officially started the

Saigoku pilgrimage. I watched other visitors and the procedure seemed

to be to throw some coins in the donation box, ring the bell twice and

pray. Lighting incense or candles requires another donation. I later

discovered that the bell should be rung three times, probably as a

reminder of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha, but perhaps some

Japanese are used to the Shinto practice of clapping twice ("to wake

the gods") before praying. There are specific chants for each

temple and a specific mantra for Kannon, but I didn't know what

they were and didn't see the point in using anything I didn't

understand. In the end I settled for a short prayer for the

health and happiness of loved ones and used this for over half

of the pilgrimage.

I have been to Ishiyamadera at least five times and always enjoyed it.

On my last visit there were some ancient images on display in the area

of the hondo behind the barrier, and visitors could pay 300 yen to go

inside and look. There was an image of Fudo Myo-o and one of Kichijoten. A couple of monks appeared and

talked to me about the temple and the images. When I asked about the

principal kannon image that is only shown every 33 years they pointed

to a dusty old poster photograph of it and informed me that it was also

displayed in the event of a royal birth. I was a bit surprised to find

serious meditation monks in a temple on the tourist route. One had been

in robes for 27 years and the other for 7 years.

I have been to Ishiyamadera at least five times and always enjoyed it.

On my last visit there were some ancient images on display in the area

of the hondo behind the barrier, and visitors could pay 300 yen to go

inside and look. There was an image of Fudo Myo-o and one of Kichijoten. A couple of monks appeared and

talked to me about the temple and the images. When I asked about the

principal kannon image that is only shown every 33 years they pointed

to a dusty old poster photograph of it and informed me that it was also

displayed in the event of a royal birth. I was a bit surprised to find

serious meditation monks in a temple on the tourist route. One had been

in robes for 27 years and the other for 7 years.

Hasedera (#8) April 2001. Hasedera was

second on my list because it also plays a part in The Tale of

Genji. Taking a limited express on the private Kintetsu line, I

switched to a local line at Yagi and got off at Hasedera station three

stops later. Following a path leading down to the river, I crossed the

bridge, turned right and walked along a street running parallel to the

river. The street used to be lined with pilgrim's lodgings, but now it

is mostly souvenir shops and several temples, one of which is a Bangai

(unnumbered pilgrimage temple).

The path eventually turned up and to the left before reaching Hasedera.

Then there were endless low steps up to the hondo. As I entered, I got

my first glimpse of the awesome eight-metre statue of Kannon towering

above on the right. A woman in front of me said, "Ah.. Sugoi!" To the

left was a raised platform opening onto a larger veranda with a

spectacular view of the valley below. At the other side of the hondo I

came across the usual statue of Binzuru and a path leading down to other

temple buildings, the pagoda and beds of peonies.

The path eventually turned up and to the left before reaching Hasedera.

Then there were endless low steps up to the hondo. As I entered, I got

my first glimpse of the awesome eight-metre statue of Kannon towering

above on the right. A woman in front of me said, "Ah.. Sugoi!" To the

left was a raised platform opening onto a larger veranda with a

spectacular view of the valley below. At the other side of the hondo I

came across the usual statue of Binzuru and a path leading down to other

temple buildings, the pagoda and beds of peonies.

In spring and autumn the temple can be crowded and there isn't much

room to stand and admire the main image. When I returned on a

subsequent visit to have my nokyocho stamped, a young man was

prostrated in front of the image and really wailing in supplication to

Kannon - an unusual sight on this pilgrimage. On another occasion, I

had come to photograph the Hase River, intending to skip the temple and

catch a taxi to nearby Muroji. But there were few people around on that

day and only one parked taxi with no driver to be seen. As it was

already late afternoon I gave up on my original plan and climbed up to

Hasedera. This time I was alone and able to spend half an hour in the

darkened hondo contemplating the ancient carving of Kannon lit by a

lantern and flickering candles.

When statues are life-size or larger they seem to have a powerful

effect on the human mind that goes beyond religious faith or devotion.

From a Buddhist perspective, this effect can be used as an inspiration

for practice. The bodhisattva ideal of enduring countless lifetimes of

suffering to help others, the piety of those who carved the image and

the devotion of the pilgrims who came to worship it down through the

centuries are all a powerful reminder of the human condition.

Although not part of the pilgrimage, Muroji

temple is not far from Hasedera and is not to be missed. It's a couple

of stops past Hasedera on the same rail line and then a local bus trip

of about 15 minutes. Muroji is a mountain temple with some fine

statuary.

Nanendo (#9) October 2001. Dating

from 813, Nanendo Hall was originally part of Kofukuji Temple, one of

the Seven Great Temples of Nara, which are briefly mentioned in the

Genji. Nanendo can be reached from Kyoto by taking a train on

the Kintetsu Line to the Nara terminus and walking for 5 minutes. The

hall is octagonal in shape and has a wisteria arbour in front, but

there's not much to see there. The main image is a Fukukensaku Kannon,

but the building is only open one day a year on October 17. The

historic Sarusawa Pond is down a flight of steps and is a pleasant

place to sit for a while. I combined the trip to Nanendo with a visit

to the nearby treasure house of Kofukuji

and to Todaiji, home of the Great

Buddha.

Nanendo (#9) October 2001. Dating

from 813, Nanendo Hall was originally part of Kofukuji Temple, one of

the Seven Great Temples of Nara, which are briefly mentioned in the

Genji. Nanendo can be reached from Kyoto by taking a train on

the Kintetsu Line to the Nara terminus and walking for 5 minutes. The

hall is octagonal in shape and has a wisteria arbour in front, but

there's not much to see there. The main image is a Fukukensaku Kannon,

but the building is only open one day a year on October 17. The

historic Sarusawa Pond is down a flight of steps and is a pleasant

place to sit for a while. I combined the trip to Nanendo with a visit

to the nearby treasure house of Kofukuji

and to Todaiji, home of the Great

Buddha.

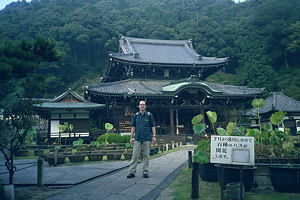

Engyoji (#27) October 2001. On my way

to Himeji Castle by bullet train I happened to notice that Engyoji

Temple was nearby and easy to reach. Luckily, there was a Tourist

Information Office at the station and within minutes I was on a bus

headed for the foot of Mount Shosha, followed by a cable car to the

top. There is a pleasant path through the forest to this large monastic

complex, with several bodhisattva statues along the way. The temple

hondo has a long veranda with a fine view of the forest, while further

up the hill is the lecture hall and courtyard that were featured in

The Last Samurai.

Engyoji (#27) October 2001. On my way

to Himeji Castle by bullet train I happened to notice that Engyoji

Temple was nearby and easy to reach. Luckily, there was a Tourist

Information Office at the station and within minutes I was on a bus

headed for the foot of Mount Shosha, followed by a cable car to the

top. There is a pleasant path through the forest to this large monastic

complex, with several bodhisattva statues along the way. The temple

hondo has a long veranda with a fine view of the forest, while further

up the hill is the lecture hall and courtyard that were featured in

The Last Samurai.

Seigantoji (#1) October 2001.

Originally one of the three temples of the syncretic Kumano faith,

Seigantoji later became the first temple of the Saigoku pilgrimage.

Although Kumano is mentioned briefly in the Genji, I was

attracted to it mainly because of the famous Nachi Falls. Situated near

the tip of the Kii Peninsula, Seigantoji is a long way from anywhere. I

took a train on the JR Kisei Line from Osaka to Kii-Katsuura, which

took several hours, and then a bus to the temple (40 minutes). I missed

the bus stop by the falls and got off at the terminus up the hill.

Nachi Taisha grand shrine is at the top of some steps and the temple is

behind it. Both were busy when I was there. At Seigantoji, the monks

were friendly and the temple sold everything a pilgrim could want. A

woman lent me her pilgrim's staff as I posed for a photograph in front

of the shrine. The falls appeared to be miles away and, worried I might

miss the bus back, I didn't walk down for a closer look. On the return

trip, I managed to catch a limited express train all the way to

Kyoto.

Seigantoji (#1) October 2001.

Originally one of the three temples of the syncretic Kumano faith,

Seigantoji later became the first temple of the Saigoku pilgrimage.

Although Kumano is mentioned briefly in the Genji, I was

attracted to it mainly because of the famous Nachi Falls. Situated near

the tip of the Kii Peninsula, Seigantoji is a long way from anywhere. I

took a train on the JR Kisei Line from Osaka to Kii-Katsuura, which

took several hours, and then a bus to the temple (40 minutes). I missed

the bus stop by the falls and got off at the terminus up the hill.

Nachi Taisha grand shrine is at the top of some steps and the temple is

behind it. Both were busy when I was there. At Seigantoji, the monks

were friendly and the temple sold everything a pilgrim could want. A

woman lent me her pilgrim's staff as I posed for a photograph in front

of the shrine. The falls appeared to be miles away and, worried I might

miss the bus back, I didn't walk down for a closer look. On the return

trip, I managed to catch a limited express train all the way to

Kyoto.

Mimurotoji (#10) October 2001.

During the Heian period, Uji was a wild and remote area south of Kyoto

where aristocrats built their country villas. By the mid-11th century,

as the "degenerate age" of Buddhism (mappo) approached, some of

the villas were converted to Amida temples. The last 10 chapters of

The Tale of Genji are set in Uji.

To reach Mimurotoji, I took a train on the Keihan Line from Kyoto and

walked for 15 minutes up the hill on the east side of the river. It's a

beautiful Chinese-style temple with pots of lotus plants in front of

the hondo and a garden full of hydrangeas lower down the hill. Beside

the belfry is a carved stone memorial to Hashihime, the deity of Uji

Bridge, which is associated with the Genji. The monks seemed to

be particularly friendly at this temple.

On one of the small paths leading down to the river I passed the Tale

of Genji Museum which was just closing.

On one of the small paths leading down to the river I passed the Tale

of Genji Museum which was just closing.

On a subsequent visit to Uji in the cherry-blossom season I spent a

whole day exploring the temples on the east side of the river, Ujigami

Shrine, and Byodo-in, one of the few

remaining Heian-era Amida halls. There is another Amida hall at Hokaiji, just north of Uji and a third at Joruriji, near Nara.

Rokuharamitsuji (#17) October

2001. By the middle of this trip I was getting enthusiastic about

the pilgrimage and decided to visit four more temples in Kyoto.

Rokuharamitsuji seemed like a good place to start because it was the

former residence of Taira Kiyomori, who presided over the end of the

Heian era and was a major character in The Tale of the Heike.

The temple is walkable from Keihan-Gojo station but I took a taxi since

it was late in the afternoon. A rather fierce-looking statue of Kannon

stands in the courtyard and a monk offered to take my photo standing

beside it. The temple's main attraction is the statuary inside,

particularly an image of Kiyomori and a unique carving of Kuya, one of

the early Amidist street-preachers, with six images of Amida coming out

of his mouth. The images are said to represent the six paramitas

(perfections) of Mahayana Buddhism.

Rokuharamitsuji (#17) October

2001. By the middle of this trip I was getting enthusiastic about

the pilgrimage and decided to visit four more temples in Kyoto.

Rokuharamitsuji seemed like a good place to start because it was the

former residence of Taira Kiyomori, who presided over the end of the

Heian era and was a major character in The Tale of the Heike.

The temple is walkable from Keihan-Gojo station but I took a taxi since

it was late in the afternoon. A rather fierce-looking statue of Kannon

stands in the courtyard and a monk offered to take my photo standing

beside it. The temple's main attraction is the statuary inside,

particularly an image of Kiyomori and a unique carving of Kuya, one of

the early Amidist street-preachers, with six images of Amida coming out

of his mouth. The images are said to represent the six paramitas

(perfections) of Mahayana Buddhism.

Kiyomizudera (#16) October 2001.

Like Ishiyamadera and Hasedera temples, Kiyomizudera was a popular

Heian pilgrimage and features in a dramatic episode in The Tale of

Genji when the distraught hero returns from the secret funeral of

his lover Yugao. I walked there after visiting other temples in

Higashiyama. The path up to the temple is lined with old houses and

gift shops, and it is common to see maiko (apprentice geisha) posing

for photos there and in front of the temple gate.

Kiyomizudera (#16) October 2001.

Like Ishiyamadera and Hasedera temples, Kiyomizudera was a popular

Heian pilgrimage and features in a dramatic episode in The Tale of

Genji when the distraught hero returns from the secret funeral of

his lover Yugao. I walked there after visiting other temples in

Higashiyama. The path up to the temple is lined with old houses and

gift shops, and it is common to see maiko (apprentice geisha) posing

for photos there and in front of the temple gate.

The temple is always crowded with tourists and pilgrims. When I

arrived, there was a long queue to pay respects to the image of Kannon

by kneeling and striking a large metal bowl rather than the usual bell

seen at most temples. The main attraction is the huge platform jutting

out over the hillside and its magnificent view over Kyoto. The temple

grounds are extensive, so I walked up to the Shinto shrine selling

lucky charms, round the side of the hill and back down to the small

waterfall. The temple is famous for both cherry blossom and Autumn

leaves - sometimes illuminated at night - but I wish there were less

visitors.

Rokkakudo (#18) October 2001.

Located a short distance southeast of Sanjo-Karasuma subway station,

Rokkakudo is easy to reach but there isn't much to look at. The temple,

which predates Kyoto by some 200 years, takes its name from the

hexagonal shape of the main hall and is the birthplace of ikebana, the

art of flower-appreciation. According to legend, when

geomancers were surveying the land for the new capital of Kyoto

they found Rokkakudo to be occupying dead centre and ordered it

to be destroyed. But a loud ringing - like a temple bell - was

heard coming from a rock in the temple grounds soon after so it was

decided to leave the temple alone. The stone is still at the

temple, marking the centre of Kyoto.

Rokkakudo (#18) October 2001.

Located a short distance southeast of Sanjo-Karasuma subway station,

Rokkakudo is easy to reach but there isn't much to look at. The temple,

which predates Kyoto by some 200 years, takes its name from the

hexagonal shape of the main hall and is the birthplace of ikebana, the

art of flower-appreciation. According to legend, when

geomancers were surveying the land for the new capital of Kyoto

they found Rokkakudo to be occupying dead centre and ordered it

to be destroyed. But a loud ringing - like a temple bell - was

heard coming from a rock in the temple grounds soon after so it was

decided to leave the temple alone. The stone is still at the

temple, marking the centre of Kyoto.

Kodo (#19) October 2001. A short train

journey and walk took me to Kodo Temple on Teramachi, a long, partly

covered street running parallel to Kawaramachi. The street has a number

of temples and is a good place to buy Buddha images, rosaries, and

other Buddhist items. This temple is the only temple on the pilgrimage

that is run by nuns, but the calligraphy entered in my pilgrim's book

at Kodo was unusually bold and dark. Rozanji

Temple, formerly the home of Murasaki Shikubu, is also on Teramachi,

not far away. There are some artifacts linked to Murasaki's family in a

small display area and bellflowers bloom in the garden in Autumn. It is

likely that Murasaki wrote parts of The Tale of Genji

here.

Kodo (#19) October 2001. A short train

journey and walk took me to Kodo Temple on Teramachi, a long, partly

covered street running parallel to Kawaramachi. The street has a number

of temples and is a good place to buy Buddha images, rosaries, and

other Buddhist items. This temple is the only temple on the pilgrimage

that is run by nuns, but the calligraphy entered in my pilgrim's book

at Kodo was unusually bold and dark. Rozanji

Temple, formerly the home of Murasaki Shikubu, is also on Teramachi,

not far away. There are some artifacts linked to Murasaki's family in a

small display area and bellflowers bloom in the garden in Autumn. It is

likely that Murasaki wrote parts of The Tale of Genji

here.

Imakumano Kannonji (#15) April

2002. The day I went to Kannonji it was raining. It was raining as

I got off the train at Tofukuji Station, raining as I walked up the

hill and pouring as I reached the temple 20 minutes later. To my

surprise, wisteria was in bloom outside the temple - the first I'd ever

seen - but the heavy rain made it difficult to take photos. As I

attempted to get a tripod shot of myself on the temple veranda, a woman

with a teenaged daughter offered to help.

Imakumano Kannonji (#15) April

2002. The day I went to Kannonji it was raining. It was raining as

I got off the train at Tofukuji Station, raining as I walked up the

hill and pouring as I reached the temple 20 minutes later. To my

surprise, wisteria was in bloom outside the temple - the first I'd ever

seen - but the heavy rain made it difficult to take photos. As I

attempted to get a tripod shot of myself on the temple veranda, a woman

with a teenaged daughter offered to help.

With the usual sign language I indicated I was looking for the Yokihi Kannon, which I knew was somewhere

in the area. She hadn't heard of it, but she asked a monk and offered

to show me the way. We trudged up the hill in pouring rain, paid

admission to the Sennyuji Temple complex

and found a small Kannon-do just inside the gate. The history of this

Kannon image goes all the way back to 8th Century China and the last

emperor of the Tang Dynasty. After falling for the beautiful concubine,

Yang Kwei-fei, the emperor neglected affairs of state and, after a

rebellion, his soldiers blamed Yang and her relatives. As they

retreated from the rebels, Yang was either strangled by a eunuch or

forced to commit suicide. The Tang Dynasty never recovered and the

emperor's remorse became the subject of a famous poem by Po Chu-i and

of numerous references in ancient Japanese literature. It is said that

the emperor missed his beloved concubine so much that he had her

sculpture made in the image of Avalokitesvara (Kannon), which was

brought to Sennyuji Temple in Kyoto by the priest Tankai in

1255.

With the usual sign language I indicated I was looking for the Yokihi Kannon, which I knew was somewhere

in the area. She hadn't heard of it, but she asked a monk and offered

to show me the way. We trudged up the hill in pouring rain, paid

admission to the Sennyuji Temple complex

and found a small Kannon-do just inside the gate. The history of this

Kannon image goes all the way back to 8th Century China and the last

emperor of the Tang Dynasty. After falling for the beautiful concubine,

Yang Kwei-fei, the emperor neglected affairs of state and, after a

rebellion, his soldiers blamed Yang and her relatives. As they

retreated from the rebels, Yang was either strangled by a eunuch or

forced to commit suicide. The Tang Dynasty never recovered and the

emperor's remorse became the subject of a famous poem by Po Chu-i and

of numerous references in ancient Japanese literature. It is said that

the emperor missed his beloved concubine so much that he had her

sculpture made in the image of Avalokitesvara (Kannon), which was

brought to Sennyuji Temple in Kyoto by the priest Tankai in

1255.

Most temples sell lucky charms known as omamori, which are

pieces of wood inside a cloth bag. This temple was the first I'd seen

where visitors could choose their own charm and put it in the bag.

Since I couldn't understand what the charms represented, my companions

chose one for me. We then walked down a hill to look at the statuary in

Sennyuji's main hall and an unusual painting of Kannon, whose eyes seem

to look directly at you, no matter where you stand. It was still

raining when we left the temple.

Yoshiminedera (#20) April 2002.

The following day I took a JR Tokaido line train to Mukomachi station

in the Oharano area southwest of Kyoto and, pressed for time, took a

taxi up to Yoshiminedera temple instead of the bus. The temple is

spread out over the side of a mountain with long walks between some of

the buildings. Although there were no images on view at the hondo, I

did pray there. There are mineral baths in the temple grounds, which

are said to be effective for those suffering from neuralgia and

lumbago, as apparently is praying at the hondo. About a year after

this, my neuralgia slowly faded away.

Yoshiminedera (#20) April 2002.

The following day I took a JR Tokaido line train to Mukomachi station

in the Oharano area southwest of Kyoto and, pressed for time, took a

taxi up to Yoshiminedera temple instead of the bus. The temple is

spread out over the side of a mountain with long walks between some of

the buildings. Although there were no images on view at the hondo, I

did pray there. There are mineral baths in the temple grounds, which

are said to be effective for those suffering from neuralgia and

lumbago, as apparently is praying at the hondo. About a year after

this, my neuralgia slowly faded away.

On the second level I found the sutra hall and a statue of Fu Daishi

(497-569), the highly respected Chinese lay Buddhist who invented

octagonal revolving sutra shelves. On this level is a 600-year-old pine

tree with a single branch extending horizontally for 150 feet. There

were several paths leading from here up the mountain but I couldn't

figure out the Japanese-language map in the temple brochure so I headed

back down to the main gate. From there I walked along the road some

distance until I came to Jurinji Temple,

where cherry blossom was in full bloom.

The woman at the ticket office spoke some English and asked what was my

interest in Jurinji. I replied that I was a fan of The Tale of

Genji, which seemed to satisfy her. The Genji contains many

references to Tales of Ise, which was written by the legendary

lover Ariwara no Narihira, who spent some time at Jurinji (the temple

is also known at Narihiradera). Behind the temple are the remains of a

kiln that Narihira used to make salt from seawater. Beside the hondo is

a room with some fine statuary, but when I pulled out my camera the

ticket-office lady came rushing in and reminded me that taking

photographs was not allowed. I looked around and saw the close-circuit

TV camera up above. There was a bus stop near the temple and a bus came

by 20 minutes later.

Miidera (#14) October 2002. Officially

known as Onjoji Temple, Miidera is on the same local rail line as

Ishiyamadera and just one stop past Hama Otsu in the direction of

Sakamoto. It's a five-minute walk from Miidera station. The temple has

a great view of Lake Biwa and extensive

grounds but is architecturally uninteresting. One attraction is the

bell that folk-hero Benkei is said to have dragged up Mount Hiei and

down again during a battle. Nearby is another bell, which has the most

beautiful sound in Japan. It was here that I set up my tripod for a

snapshot.

Miidera (#14) October 2002. Officially

known as Onjoji Temple, Miidera is on the same local rail line as

Ishiyamadera and just one stop past Hama Otsu in the direction of

Sakamoto. It's a five-minute walk from Miidera station. The temple has

a great view of Lake Biwa and extensive

grounds but is architecturally uninteresting. One attraction is the

bell that folk-hero Benkei is said to have dragged up Mount Hiei and

down again during a battle. Nearby is another bell, which has the most

beautiful sound in Japan. It was here that I set up my tripod for a

snapshot.

Murasaki Shikibu's brother was an abbot of Miidera Temple, which is

probably why her father took vows there. In its heyday the temple was a

rival to Enryakuji on sacred Mount Hiei

and the monks sometimes fought with each other. They were also not

above marching on the capital to extract demands from the emperor.

Mount Hiei is a pilgrimage in its own right and well worth a day's

visit. There is a cable car from Sakamoto, further up the line from

Miidera station.

Iwamadera (#12) October 2002.

The bus for Iwamadera leaves once in a blue moon and doesn't go all the

way to the temple. The walk would be well over an hour, uphill, with no

signs in English. This is why I had put off going there for so long. In

the end I made a spur-of-the-moment decision to go there while visiting

nearby Ishiyamadera. There are always plenty of taxis waiting outside

Ishiyamadera, so I took one of those and had the driver wait at the

temple. It cost around 5,000 yen for the round-trip.

Iwamadera (#12) October 2002.

The bus for Iwamadera leaves once in a blue moon and doesn't go all the

way to the temple. The walk would be well over an hour, uphill, with no

signs in English. This is why I had put off going there for so long. In

the end I made a spur-of-the-moment decision to go there while visiting

nearby Ishiyamadera. There are always plenty of taxis waiting outside

Ishiyamadera, so I took one of those and had the driver wait at the

temple. It cost around 5,000 yen for the round-trip.

When I arrived a monk - perhaps the abbot - was sitting at the entrance

so I took a couple of photographs. A little later he indicated that

there was a bamboo forest behind the temple, so I went to take a look.

I spent so much time admiring the view that I completely forgot to look

for the pond that inspired Basho's famous haiku about the sound of a

frog jumping into the water. But it turned out later that I did at

least get a photo of it.

Sojiji (#22) November 2003.

I had saved Sojiji and Anaoji temples for a rainy day and the rain fell

constantly during the first four days of this November trip to Kyoto. I

took a train on the Hankyu Kyoto line for Sojiji station and walked 400

metres to the temple. There is an ugly, modern car park outside the

main gate and the temple courtyard is covered with dark gravel. All in

all, pretty uninspiring so I didn't stay for long.

Sojiji (#22) November 2003.

I had saved Sojiji and Anaoji temples for a rainy day and the rain fell

constantly during the first four days of this November trip to Kyoto. I

took a train on the Hankyu Kyoto line for Sojiji station and walked 400

metres to the temple. There is an ugly, modern car park outside the

main gate and the temple courtyard is covered with dark gravel. All in

all, pretty uninspiring so I didn't stay for long.

Anaoji (#21) November 2003. Anaoji is

reached by taking a JR Sanin Line train to Kameoka station. The scenery

on this route is pretty wild considering it isn't that far from Kyoto.

Because of the rain, I took a taxi from the station and had the driver

wait. There isn't much at Anaoji other than a small tahoto and a few

small maple trees. A carving of a reclining Buddha is sometimes

displayed but it wasn't on view when I was there.

Anaoji (#21) November 2003. Anaoji is

reached by taking a JR Sanin Line train to Kameoka station. The scenery

on this route is pretty wild considering it isn't that far from Kyoto.

Because of the rain, I took a taxi from the station and had the driver

wait. There isn't much at Anaoji other than a small tahoto and a few

small maple trees. A carving of a reclining Buddha is sometimes

displayed but it wasn't on view when I was there.

Fujiidera (#5) April 2004.

A few temples on the Saigoku Pilgrimage have lodgings for pilgrims, but

a foreigner would have difficulty making a booking. To get a feel of

how the pilgrimage used to be, I headed for Mount Koya, the centre of

Shingon Buddhism, where nine temples offer lodgings for non-Japanese.

Taking a Keihan line train to Osaka's Yodobashi Station, I switched to

the Mido-suji subway line and got off at Namba. From there I walked

through to Nankai Namba station and caught the limited express to

Koyasan. The last stop is Gokurakubashi, which means "Bridge to

Paradise," and then it's a cable car to the top of the

mountain and a bus into the village.

Fujiidera (#5) April 2004.

A few temples on the Saigoku Pilgrimage have lodgings for pilgrims, but

a foreigner would have difficulty making a booking. To get a feel of

how the pilgrimage used to be, I headed for Mount Koya, the centre of

Shingon Buddhism, where nine temples offer lodgings for non-Japanese.

Taking a Keihan line train to Osaka's Yodobashi Station, I switched to

the Mido-suji subway line and got off at Namba. From there I walked

through to Nankai Namba station and caught the limited express to

Koyasan. The last stop is Gokurakubashi, which means "Bridge to

Paradise," and then it's a cable car to the top of the

mountain and a bus into the village.

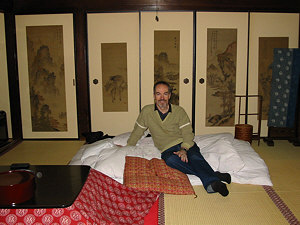

By the time I arrived at Shojoshinin

Temple, my lodgings for the next two nights, it was getting dark. The

temple is situated on the edge of the huge forest-cemetary that

surrounds the Okunoin where Kobo Daishi, the founder of Shingon

Buddhism, is entombed, so I decided to take a walk. The path to the Okuno-in is lit up but it was so misty that I

turned back because I could hardly see where I was going. At the temple

I discovered I had a room on the ground floor beside a pond and

wisteria arbour. There were painted panels separating the rooms but no

locks of any kind on the sliding wooden doors. I noticed that one of

the paintings was of the Tang Dynasty poet, Li Po, gazing into a

waterfall with a servant hanging on to him (legend has it that he

drowned while drunk and trying to embrace the reflection of the moon in

a river). I had the curious feeling that I belonged in that

room. After relaxing in a hot wooden bath for a while, I got under the

futon (the temperature drops considerably at night) and spent a couple

of hours listening to Mozart on my Walkman.

By the time I arrived at Shojoshinin

Temple, my lodgings for the next two nights, it was getting dark. The

temple is situated on the edge of the huge forest-cemetary that

surrounds the Okunoin where Kobo Daishi, the founder of Shingon

Buddhism, is entombed, so I decided to take a walk. The path to the Okuno-in is lit up but it was so misty that I

turned back because I could hardly see where I was going. At the temple

I discovered I had a room on the ground floor beside a pond and

wisteria arbour. There were painted panels separating the rooms but no

locks of any kind on the sliding wooden doors. I noticed that one of

the paintings was of the Tang Dynasty poet, Li Po, gazing into a

waterfall with a servant hanging on to him (legend has it that he

drowned while drunk and trying to embrace the reflection of the moon in

a river). I had the curious feeling that I belonged in that

room. After relaxing in a hot wooden bath for a while, I got under the

futon (the temperature drops considerably at night) and spent a couple

of hours listening to Mozart on my Walkman.

At 6am I attended a service in the temple hall, which was mostly

chanting prayers for ancestors, and then had breakfast in my room. At

Shojoshinin, no food or drink is allowed in from outside but the monks

serve delicious vegetarian food with green tea for breakfast and

dinner. The main attractions of Mount Koya are the Garan, Kongobuji, the treasure house and

the Okunoin, but there are plenty of other temples to visit.

The following day I headed back to Osaka. From Osaka's Tennoji station

I took a local on the Kintetsu Osaka line to Fujiidera station in the

suburbs. Fujiidera temple is a few minutes walk through a shopping

arcade. The first thing I noticed was wisteria blooming in great

profusion around the temple - both lavender and white varieties. In

front of the hondo there was a stone prayer wheel and one of the ugly

Hitatchi signs that are common in temple courtyards. The

principal image at Fujiidera is a remarkable thousand-armed Kannon -

one of the few that really has a thousand arms - but it is

only displayed on the 18th of the month.

The following day I headed back to Osaka. From Osaka's Tennoji station

I took a local on the Kintetsu Osaka line to Fujiidera station in the

suburbs. Fujiidera temple is a few minutes walk through a shopping

arcade. The first thing I noticed was wisteria blooming in great

profusion around the temple - both lavender and white varieties. In

front of the hondo there was a stone prayer wheel and one of the ugly

Hitatchi signs that are common in temple courtyards. The

principal image at Fujiidera is a remarkable thousand-armed Kannon -

one of the few that really has a thousand arms - but it is

only displayed on the 18th of the month.

Tsubosakadera (#6) April 2004.

Tsubosakadera was a relatively easy train ride on the Kintetsu

Kashihara line south of Nara, Yamato Yagi and Kashihara Jingumae. A

short bus ride took me to the temple gate. The first building I entered

was the Jogando, made from white stone and reminiscent of an Indian

cave temple. There is nothing else like it on the pilgrimage. On the

next level is the hondo, containing a very Indian-style Senju Kannon.

Visitors are able to get very close to the image and a friendly monk

sits nearby explaining the history of the temple, which is famous for

its work with the blind and help for lepers in India.

Tsubosakadera (#6) April 2004.

Tsubosakadera was a relatively easy train ride on the Kintetsu

Kashihara line south of Nara, Yamato Yagi and Kashihara Jingumae. A

short bus ride took me to the temple gate. The first building I entered

was the Jogando, made from white stone and reminiscent of an Indian

cave temple. There is nothing else like it on the pilgrimage. On the

next level is the hondo, containing a very Indian-style Senju Kannon.

Visitors are able to get very close to the image and a friendly monk

sits nearby explaining the history of the temple, which is famous for

its work with the blind and help for lepers in India.

The temple has other attractions - a long wall of stone carvings

depicting Jataka Tales from the Buddha's former lives, a copy of a 1st

century stone carving from Amaravati, a 15th century pagoda and a

20-metre stone sculpture of Kannon. At a small shop in the temple

grounds a woman asked how I had got there and seemed impressed that I'd

used public transport, perhaps because I was limping a little from a

recently sprained ankle.

Kokawadera (#3) September 2004.

By September 2004 I had developed a serious interest in Buddhism and

was meditating regularly. This put a new perspective on the pilgrimage

for me. I was now more interested in the religious practices and

symbolism I encountered at the temples and in the differences between

the Theravada school of Southeast Asia and the Mahayana school that

Japanese Buddhists belong to. With regard to Kannon, I had found John

Blofeld's book on The Bodhisattva of Compassion particularly

helpful in understanding the difference between popular worship of this

so-called "goddess" and the higher-level meditation practice of

visualising the Bodhisattva Avalokitasvara.

Kokawadera (#3) September 2004.

By September 2004 I had developed a serious interest in Buddhism and

was meditating regularly. This put a new perspective on the pilgrimage

for me. I was now more interested in the religious practices and

symbolism I encountered at the temples and in the differences between

the Theravada school of Southeast Asia and the Mahayana school that

Japanese Buddhists belong to. With regard to Kannon, I had found John

Blofeld's book on The Bodhisattva of Compassion particularly

helpful in understanding the difference between popular worship of this

so-called "goddess" and the higher-level meditation practice of

visualising the Bodhisattva Avalokitasvara.

I went to Kokawadera after another visit to Mount Koya. Typhoon Niju

had passed through while I was staying in a temple on the mountain and

it was pretty wild for a night. But it was sunny again as I took the

train to Hashimoto and switched to the Wakayama Line for Kokawa

Station. The temple wasn't hard to find. Since it was so hot, I bought

some green tea ice cream and sat down to eat it at a small shop beside

the temple's wide gravel courtyard.

I went to Kokawadera after another visit to Mount Koya. Typhoon Niju

had passed through while I was staying in a temple on the mountain and

it was pretty wild for a night. But it was sunny again as I took the

train to Hashimoto and switched to the Wakayama Line for Kokawa

Station. The temple wasn't hard to find. Since it was so hot, I bought

some green tea ice cream and sat down to eat it at a small shop beside

the temple's wide gravel courtyard.

As I enjoyed my ice cream, an enormous centipede appeared from under a

cupboard and made a beeline for the backpack I had left on the floor. I

called and pointed it out to the old lady who ran the shop. Chuckling

at the idea of the centipede getting in my backpack, she selected a

large cleaver and proceeded to chop the unfortunate creature into

little pieces - a bit alarming considering this was in the grounds of a

Buddhist temple.

In the hondo, I recited the Three Refuges - a way of remaining mindful

of the importance of the Buddha, the Dharma (teachings) and the Sangha

(monastics) while cultivating the mind. In fact, the real purpose of

any Buddhist ritual is to improve one's mental state. If the symbolism

of the action isn't understood, it's pointless. Even lighting three

incense sticks or ringing a temple bell three times is a way to remind

oneself of the Three Refuges.

In the hondo, I recited the Three Refuges - a way of remaining mindful

of the importance of the Buddha, the Dharma (teachings) and the Sangha

(monastics) while cultivating the mind. In fact, the real purpose of

any Buddhist ritual is to improve one's mental state. If the symbolism

of the action isn't understood, it's pointless. Even lighting three

incense sticks or ringing a temple bell three times is a way to remind

oneself of the Three Refuges.

After spending some time in the hondo, I headed up to the level above

where I found a Chinese gate leading to a small garden and lily pond.

The pond contained the type of water hyacinth that clogs the canals and

rivers of Southeast Asia, but it didn't look so menacing flowering in

the small pool.

Kimiidera (#2) October 2004.

Continuing on the Wakayama line to Wakayama City, I changed

to a local on the JR Kisei line for the short journey to Kimiidera

station. The temple was half a kilometre south of the station. The area

seemed almost Mediterranean in the midday sun with white buildings,

palm trees and few people walking around. The temple had a fine view of

the sea, looking out towards Awaji Island, but

was otherwise unremarkable. It's main attraction is the

early-blossoming cherry trees in front of the hondo. An ugly,

Chinese-style building stood in the temple grounds although I couldn't

figure out what it was. As I walked back to the station, a couple of

tiny tots in school uniform approached me and said, "Harro." When I

replied, they said, "Ah! Sugoi!" From Kimiidera station it was

back to Wakayama station and then a train straight through to

Kyoto.

Kimiidera (#2) October 2004.

Continuing on the Wakayama line to Wakayama City, I changed

to a local on the JR Kisei line for the short journey to Kimiidera

station. The temple was half a kilometre south of the station. The area

seemed almost Mediterranean in the midday sun with white buildings,

palm trees and few people walking around. The temple had a fine view of

the sea, looking out towards Awaji Island, but

was otherwise unremarkable. It's main attraction is the

early-blossoming cherry trees in front of the hondo. An ugly,

Chinese-style building stood in the temple grounds although I couldn't

figure out what it was. As I walked back to the station, a couple of

tiny tots in school uniform approached me and said, "Harro." When I

replied, they said, "Ah! Sugoi!" From Kimiidera station it was

back to Wakayama station and then a train straight through to

Kyoto.

I had timed this particular trip so that I would be in Kyoto for the

Harvest Moon Festival and I wasn't disappointed. The moon-viewing at Daikakuji Temple and the bugaku performance at

Shimogamo Shrine are both

excellent.

Okadera (#7) April 2005.

Okadera station doesn't have a bus service to the temple anymore. The

best way to get there is Kintetsu Kashihara line to Kashihara

Jingumae and then bus, or a little further down the line to Asuka

station and then rent a bicycle. My knees don't like cycling so I took

a taxi to the temple and had the driver wait. The hondo was large and

the principal image was an unusual 8th century Nyorin Kannon - Japan's

largest clay sculpture.

Okadera (#7) April 2005.

Okadera station doesn't have a bus service to the temple anymore. The

best way to get there is Kintetsu Kashihara line to Kashihara

Jingumae and then bus, or a little further down the line to Asuka

station and then rent a bicycle. My knees don't like cycling so I took

a taxi to the temple and had the driver wait. The hondo was large and

the principal image was an unusual 8th century Nyorin Kannon - Japan's

largest clay sculpture.

I continued on to nearby Asukadera,

Japan's first Buddhist temple, founded in the 6th century. What's left

of the temple is quite modest, but it still houses the country's oldest

existing Buddha image, a bronze sculpture of Shakyamuni cast by Tori Busshi in

609.

Kami Daigoji (#11) April 2005.

Although I had visited Daigoji before to see the procession celebrating

Hideyoshi's famous cherry-blossom party, I had never climbed up to Kami

Daigoji at the top of the mountain. This was mainly because the

guidebook described the path as so steep that that a rope was provided

to pull oneself up. It sounded daunting for someone with sore knees and

chronic ankle pain - but it had to be done sometime or other. So, one

sunny day when cherry trees were in blossom, I took the Tozai line

subway from Kyoto to Daigo station and then walked for 10-15

minutes to the temple gate.

Kami Daigoji (#11) April 2005.

Although I had visited Daigoji before to see the procession celebrating

Hideyoshi's famous cherry-blossom party, I had never climbed up to Kami

Daigoji at the top of the mountain. This was mainly because the

guidebook described the path as so steep that that a rope was provided

to pull oneself up. It sounded daunting for someone with sore knees and

chronic ankle pain - but it had to be done sometime or other. So, one

sunny day when cherry trees were in blossom, I took the Tozai line

subway from Kyoto to Daigo station and then walked for 10-15

minutes to the temple gate.

There were a lot of people entering the main gate as I arrived.

Daigoji features one of the two surviving

5-storey Heian-era pagodas in Japan and the oldest wooden structure in

Kyoto prefecture. It's in remarkably good condition for a pagoda built

in 951. Other attractions are a large main hall, the Sambo-in, garden

and treasure house. No photographs allowed in the garden,

unfortunately. Walking towards the mountain I passed a picturesque

shrine to Benten at the far side of a pond and then entered the

forest.

The path was steep, but it wasn't horrendous. For a start it was mostly

logs set into the earth rather than steep steps, and the rope in the

centre of the path seemed designed to separate people going up from

those coming down. It can be quite busy when the cherry blossom is

in bloom. Half way up there is a sacred waterfall and some benches. A

man gave me some candies as I sat admiring the view. The path through

the forest is a very pleasant one. It's wide and it isn't at all

gloomy. Near the top, a monk filled my bottle with water from the

temple spring. It had taken me about an hour at a fairly leisurely

pace. The walk through the forest had left me feeling uplifted and

I felt energized as I entered the Junteido. This is how a pilgrimage

should feel and though there was no image on display I did a

spontaneous metta meditation for all beings. For the first time I

really knew what the pilgrimage is about. It's a way to purify the

mind, to improve one's mental state, if only for a short time.

The path was steep, but it wasn't horrendous. For a start it was mostly

logs set into the earth rather than steep steps, and the rope in the

centre of the path seemed designed to separate people going up from

those coming down. It can be quite busy when the cherry blossom is

in bloom. Half way up there is a sacred waterfall and some benches. A

man gave me some candies as I sat admiring the view. The path through

the forest is a very pleasant one. It's wide and it isn't at all

gloomy. Near the top, a monk filled my bottle with water from the

temple spring. It had taken me about an hour at a fairly leisurely

pace. The walk through the forest had left me feeling uplifted and

I felt energized as I entered the Junteido. This is how a pilgrimage

should feel and though there was no image on display I did a

spontaneous metta meditation for all beings. For the first time I

really knew what the pilgrimage is about. It's a way to purify the

mind, to improve one's mental state, if only for a short time.

About 20 minutes' walk north of Daigoji is the charming

Zuishin-in, the temple where legendary

Heian-era poet Ono no Komachi spent the last years of her life. It's

worth a look, although access is a bit easier from Ono station, one

stop north of Daigo station.

Hogonji (#30) November 2005.

I had been leaving the hard-to-reach temples till last, so November

2005 was when I got smart and asked the Tourist Information Office for

details on how to reach them. They can usually print out full details,

including bus schedules, if you tell them exactly when you want to go.

Hogonji is on Chikubushima Island in Lake Biwa, but it proved quite

easy to get to. I took the JR Kosei line to Omi-Imazu station, from

where it was a three-minute walk to the ferry. Ferries leave once an

hour and the deal is you buy a round-trip ticket, stay on the island

one hour and return on the boat you arrived on. The boat trip takes

about 30 minutes.

It was a sunny day and the lake was relatively calm, but in bad weather

the waves can be ferocious and the temple keeps a register of pilgrims

who died making the trip in former times. The island is just a

tree-covered rock with a small harbour on one side. From the harbour I

headed straight up some steps to the left and reached the large

Benten Hall and pagoda. From there I went back down more steps to the

unusual hondo with its thatched roof and carved doorway. From there an

open corridor leads to Tsukubusuma Shrine, and beneath the shrine is a

platform where you can throw clay disks into the sea, supposedly taking

your bad karma with them. The only other place I've seen clay disk

throwing is at Jingoji Temple west of

Kyoto.

Hogonji (#30) November 2005.

I had been leaving the hard-to-reach temples till last, so November

2005 was when I got smart and asked the Tourist Information Office for

details on how to reach them. They can usually print out full details,

including bus schedules, if you tell them exactly when you want to go.

Hogonji is on Chikubushima Island in Lake Biwa, but it proved quite

easy to get to. I took the JR Kosei line to Omi-Imazu station, from

where it was a three-minute walk to the ferry. Ferries leave once an

hour and the deal is you buy a round-trip ticket, stay on the island

one hour and return on the boat you arrived on. The boat trip takes

about 30 minutes.

It was a sunny day and the lake was relatively calm, but in bad weather

the waves can be ferocious and the temple keeps a register of pilgrims

who died making the trip in former times. The island is just a

tree-covered rock with a small harbour on one side. From the harbour I

headed straight up some steps to the left and reached the large

Benten Hall and pagoda. From there I went back down more steps to the

unusual hondo with its thatched roof and carved doorway. From there an

open corridor leads to Tsukubusuma Shrine, and beneath the shrine is a

platform where you can throw clay disks into the sea, supposedly taking

your bad karma with them. The only other place I've seen clay disk

throwing is at Jingoji Temple west of

Kyoto.

Chomeiji (#31) November 2005.

Chomeiji overlooks Lake Biwa from the eastern side. It's another temple

that requires a train and bus journey from Kyoto. The day was overcast

when I started up the 808 steep stone steps that lead through the

forest to the temple. With no sun and overhanging trees it was a gloomy

climb. As is often the case with mountain temples, pilgrims who have

their own transport can get closer to the temple and don't have to walk

as far. A group of pilgrims arrived at the same time as me, having

jumped out of a minibus not far from the top of the mountain. They lit

candles and chanted in front of the Kannon image in the hondo as I

admired the view and waited for them to leave. I love quiet

mountain temples and the Japanese do tend to be noisy in

groups.

Chomeiji (#31) November 2005.

Chomeiji overlooks Lake Biwa from the eastern side. It's another temple

that requires a train and bus journey from Kyoto. The day was overcast

when I started up the 808 steep stone steps that lead through the

forest to the temple. With no sun and overhanging trees it was a gloomy

climb. As is often the case with mountain temples, pilgrims who have

their own transport can get closer to the temple and don't have to walk

as far. A group of pilgrims arrived at the same time as me, having

jumped out of a minibus not far from the top of the mountain. They lit

candles and chanted in front of the Kannon image in the hondo as I

admired the view and waited for them to leave. I love quiet

mountain temples and the Japanese do tend to be noisy in

groups.

Kannonshoji (#32) November 2005.

Kannonshoji is also on the eastern side of Lake Biwa. After taking a

train on the JR Tokaido line to Notogawa, I exited the station and

jumped on a bus that left immediately for the temple. If you miss an

upcountry bus it will usually mean an hour's wait for the next one. I

informed the driver I was going to Kannonshoji so that he would make

sure I didn't miss the stop. And 45 minutes later he let me off at a

quiet village intersection and pointed to the right. I followed the

road for about 150 metres and came to a torii. There were signs

pointing left so I started down a road to the left, but a man standing

by the torii called out to me and pointed behind him. Inside the shrine

grounds was a narrow path leading up the mountain, and apparently that

was the way to the temple.

Kannonshoji (#32) November 2005.

Kannonshoji is also on the eastern side of Lake Biwa. After taking a

train on the JR Tokaido line to Notogawa, I exited the station and

jumped on a bus that left immediately for the temple. If you miss an

upcountry bus it will usually mean an hour's wait for the next one. I

informed the driver I was going to Kannonshoji so that he would make

sure I didn't miss the stop. And 45 minutes later he let me off at a

quiet village intersection and pointed to the right. I followed the

road for about 150 metres and came to a torii. There were signs

pointing left so I started down a road to the left, but a man standing

by the torii called out to me and pointed behind him. Inside the shrine

grounds was a narrow path leading up the mountain, and apparently that

was the way to the temple.

The walk to Kannonshoji is one of the highlights of the pilgrimage. It

isn't so steep you have to look down at the ground and it is lightly

wooded so it isn't gloomy. Although it takes an hour, it's a very

pleasant walk with an occasional view. Towards the top of the mountain

there are small stone figures of Kannon and Jizo beside the path, then

the dirt path turns into a gravel path and the temple entrance with its

black nio guardians appears. The temple burnt down in 1993 and

reconstruction of the hondo was only completed in 2004. The new

principal image, a seated Fukukensaku Kannon, is six metres high and

was carved from a 23-tonne block of sandalwood imported from

India.

Although impressive, the huge image didn't resonate much with me.

Modern sculptors generally can't produce the beautiful facial features

that centuries-old images possess. And the power of an image as a lot

to do with knowing that hundreds of thousands of pilgrims have

worshipped before it over hundreds of years.

Although impressive, the huge image didn't resonate much with me.

Modern sculptors generally can't produce the beautiful facial features

that centuries-old images possess. And the power of an image as a lot

to do with knowing that hundreds of thousands of pilgrims have

worshipped before it over hundreds of years.

The legend of Kannonshoji is that a merman asked a young nobleman to

found a temple dedicated to Kannon so that he could pray for a better

rebirth. A scene from this legend is depicted on a wall made from large

boulders beside the hondo with Kannon standing at the edge of a "cliff"

and the merman praying far below. There is a fine view of the valley

below from the other side of the hondo and statues of Amida and the

nobleman of the legend are silhouetted against the sky.

When I reached the bus stop at the bottom of the mountain again, the

intersection was deserted. After 10 minutes the bus from Notogawa

arrived and a Japanese passenger got off. He stood in the middle of the

intersection looking down each road and scratching his head. He didn't

look like a pilgrim or day-tripper but he seemed to be in a hurry.

Eventually, he asked if I could speak Japanese. I said I didn't. Then

he said, "Kannonshoji?" I nodded and pointed towards the torii. He

bowed several times and hurried off. Not many Japanese go to remote

temples alone and without maps so assumed he had some urgent request to

make of Kannon.

Makinoodera (#4) April 2006.

In 2006 I went Kyoto late in April in the hope of seeing some wisteria,

but unusually cold weather resulted in my arriving right in the middle

of cherry-blossom season. The blossom made the five pilgrimage temples

I visited so much brighter. The first on my list was Makinoodera, on

the way to Wakayama and not easy to reach. From Kyoto I took the JR

Sanyo line, the Osaka Loop line and then the Nankai line to Izumi-Otsu

station, where I took a Nankai bus to Makinoo-san. After an hour on the

bus I was left at a fork in the road. The bus took the right fork and

the driver had indicated I should take the left fork. There was a large

sign for Sefukuji Temple, which I didn't know at the time was the more

popular name for Makinoodera.

Makinoodera (#4) April 2006.

In 2006 I went Kyoto late in April in the hope of seeing some wisteria,

but unusually cold weather resulted in my arriving right in the middle

of cherry-blossom season. The blossom made the five pilgrimage temples

I visited so much brighter. The first on my list was Makinoodera, on

the way to Wakayama and not easy to reach. From Kyoto I took the JR

Sanyo line, the Osaka Loop line and then the Nankai line to Izumi-Otsu

station, where I took a Nankai bus to Makinoo-san. After an hour on the

bus I was left at a fork in the road. The bus took the right fork and

the driver had indicated I should take the left fork. There was a large

sign for Sefukuji Temple, which I didn't know at the time was the more

popular name for Makinoodera.

After a short while there was a T-junction and an arrow pointed right.

Pretty soon I was walking down a pleasant forest road beside a stream.

After 20 minutes I was getting a bit worried that I might be going in

the wrong direction so I asked a woman I met walking towards me. It

turned out she was collecting plants and a couple of minutes after we

parted she drove up in her car and gave me a lift to the base of the

mountain. The temple was a punishing half-hour climb up steep and

narrow steps, and the overhanging trees made it gloomy. But at the top

there were cherry trees in full blossom and a stunning view of the

surrounding mountains.

I had the place to myself for half an hour and then a pilgrim tour

group arrived led by a priest. They were very friendly, taking my photo

with the group and then waving goodbye as I headed back down the

mountain. An hour later their tour bus passed me as I was almost at the

bus stop. They all waved again. They probably thought I was lonely,

hiking in the mountains on my own.

Katsuoji (#23) April 2006.

Katsuoji is another temple that is awkward to get to because of

infrequent buses. I took trains to Shin-Osaka, Esaka and Senri-Chuo,

and then switched to a Hankyu bus for the 45-minute ride through Osaka

suburbs to the temple gates. There was cherry blossom everywhere. A

path leads through the main gate, past a pond and up to a tahoto. To

the left of the tahoto is another path leading to the hondo and beside

the path is an enclosure full of red Daruma dolls. Daruma is the

Japanese word for Bodhidarma, the Indian monk who first brought Zen

Buddhism to China. The dolls have a spherical shape because it is said

that Bodhidarma meditated for so long that his arms and legs fell

off.

Katsuoji (#23) April 2006.

Katsuoji is another temple that is awkward to get to because of

infrequent buses. I took trains to Shin-Osaka, Esaka and Senri-Chuo,

and then switched to a Hankyu bus for the 45-minute ride through Osaka

suburbs to the temple gates. There was cherry blossom everywhere. A

path leads through the main gate, past a pond and up to a tahoto. To

the left of the tahoto is another path leading to the hondo and beside

the path is an enclosure full of red Daruma dolls. Daruma is the

Japanese word for Bodhidarma, the Indian monk who first brought Zen

Buddhism to China. The dolls have a spherical shape because it is said

that Bodhidarma meditated for so long that his arms and legs fell

off.

I never found the temple's famous 2.5-metre sandalwood carving of

Kannon, which I think was in a new hondo that is only open to the

public on the 18th of the month. There were paths leading up into the

forest but I didn't feel like exploring because of the heavy

rain.

Ichijoji (#26) April 2006.

Ichijoji wasn't as hard as I expected - a JR Tokaido line train

straight through to Himeji station and then 35 minutes on a Shinki bus

to the temple gates. Again, lots of cherry blossom but unfortunately

the temple hondo was closed for renovation. Ichijoji's attractions

include a three-tiered pagoda dating from 1171 and a statue of Hodo

Sennin, one of the Chinese Immortals. Below the hondo is a quiet pond

and some old gravestones.

Ichijoji (#26) April 2006.

Ichijoji wasn't as hard as I expected - a JR Tokaido line train

straight through to Himeji station and then 35 minutes on a Shinki bus

to the temple gates. Again, lots of cherry blossom but unfortunately

the temple hondo was closed for renovation. Ichijoji's attractions

include a three-tiered pagoda dating from 1171 and a statue of Hodo

Sennin, one of the Chinese Immortals. Below the hondo is a quiet pond

and some old gravestones.

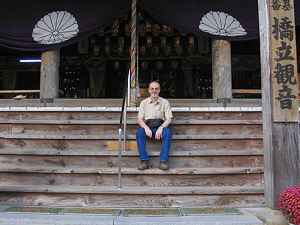

Kiyomizudera (Hyogo) (#25)

April 2006.

I had been dreading the trip to Kiyomizudera in Hyogo because it is

remote and there are very few buses. Taking the JR Tokaido line to

Amagasaki, I switched to the JR Fukuchiyama line and got off at Aino

station. Aino is a bleak town situated in a long valley. Bitter winds

and drizzle made for a freezing day and there was no shelter at the bus

stop. Eventually the No. 52 bus came and I got on with a Japanese

couple. We were the only passengers and I hoped they were going to the

temple. But they got off at the Hyogo Ceramics Museum, which was in the

middle of nowhere and looked utterly deserted.

Kiyomizudera (Hyogo) (#25)

April 2006.

I had been dreading the trip to Kiyomizudera in Hyogo because it is

remote and there are very few buses. Taking the JR Tokaido line to

Amagasaki, I switched to the JR Fukuchiyama line and got off at Aino

station. Aino is a bleak town situated in a long valley. Bitter winds

and drizzle made for a freezing day and there was no shelter at the bus

stop. Eventually the No. 52 bus came and I got on with a Japanese

couple. We were the only passengers and I hoped they were going to the

temple. But they got off at the Hyogo Ceramics Museum, which was in the

middle of nowhere and looked utterly deserted.

The bus took several turns on the half-hour journey so I knew I would

never be able to walk back if I missed the last bus from the temple. We

arrived at the base of the mountain, which looked like a small

terminus, and the bus driver announced it was Kiyomizudera. But as soon

as I got off the bus roared off up a road leading up the mountain!

There was a tollgate in the centre of the road so I tried to talk to

the two women manning the booth. They gave me an English leaflet about

the temple and pointed to a path leading into the trees. I was a bit

concerned because it was 1.15pm and I knew the last bus left the temple

at 2.15. I had expected to have an hour to look around and there I was

at the foot of the mountain.

The rocky path turned out to be an old pilgrim's trail that went round

the back of the mountain, and as with the path to Kannonshoji, it

really provided a taste of the original Kannon pilgrimage. At the

back of the mountain the wind was really howling and the sky was

dark, but it didn't rain. Near the top I passed a stone statue of

Jizo and then came upon a long series of stone steps, with carved

lions at either side, that seemed to lead to nowhere. However, just

through the trees was an entrance to the temple grounds. The walk had

taken about 45 minutes.

The rocky path turned out to be an old pilgrim's trail that went round

the back of the mountain, and as with the path to Kannonshoji, it

really provided a taste of the original Kannon pilgrimage. At the

back of the mountain the wind was really howling and the sky was

dark, but it didn't rain. Near the top I passed a stone statue of

Jizo and then came upon a long series of stone steps, with carved

lions at either side, that seemed to lead to nowhere. However, just

through the trees was an entrance to the temple grounds. The walk had

taken about 45 minutes.

Without looking at the temple leaflet I headed over to the niomon (main

gate with two nio guardians) at the front of the mountain where I

thought the pilgrim's office and bus stop must be. In front of the

niomon was a huge, deserted parking lot but no pilgrim's office in

site. A woman saw me scratching my head and came out of her souvenir

shop. She indicated that the pilgrim's office was at the back of

the mountain and then took me to the bus stop where a bus was just

arriving. For a while it looked like I would have to leave on this last

bus without a stamp in my book, but the driver assured me there was

another bus at 4.30.

With over an hour to spare, I headed back to the Daikodo (lecture hall)

to see the Kannon image and have my book stamped. It was so cold the

monks were using electric heaters inside. I then took a look at the

priest's quarters and the moon-viewing pavilion. The ancient pagoda

had disappeared - only the stone foundations were visible - possibly

dismantled for renovation. After taking a short detour through the

forest I found the Okagenoido Well, but not much else, so I walked back

to the niomon expecting a 35-minute wait for the bus. The souvenir lady

seemed very surprised to see me and pointed back the way I'd come from.

OK, now I got it - the next bus would leave from the bottom of the

mountain, not the top. So back I went down the old pilgrim's trail

again, grateful in a way that circumstances had forced me to take this

picturesque path twice. My guidebook says this temple is "hard to

reach and even harder to leave - it doesn't invite lingering," and that

may be true but the path through the forest is really the main

attraction. I reached the bus stop with a few minutes to spare and was

on the bus just before it started to rain.

Nakayamadera (#24) April 2006.

Nakayamadera was a few stops down the line from Aino and since I had

read it was a busy neighbourhood temple I decided to chance it and hope

it was open later than the usual 5pm. Once out of Nakayamadera station,

I headed down an alley where a man on a bicycle pointed out the way to

the temple for me. The alley went round a pond, over the railway lines

and along to another station. The temple gate was just round the

corner. As I walked through the niomon at 5.40 a guard was looking at

his watch and all the buildings looked closed. But luckily the

pilgrim's office was open so I was able to have my book

stamped. It almost seemed like I'd had Kannon's help on this

particular day.

Nakayamadera (#24) April 2006.

Nakayamadera was a few stops down the line from Aino and since I had

read it was a busy neighbourhood temple I decided to chance it and hope

it was open later than the usual 5pm. Once out of Nakayamadera station,

I headed down an alley where a man on a bicycle pointed out the way to

the temple for me. The alley went round a pond, over the railway lines

and along to another station. The temple gate was just round the

corner. As I walked through the niomon at 5.40 a guard was looking at

his watch and all the buildings looked closed. But luckily the

pilgrim's office was open so I was able to have my book

stamped. It almost seemed like I'd had Kannon's help on this

particular day.

Like all Japanese temples that are known to assure women of an easy

childbirth, Nakayamadera has plenty of money. Most of the buildings are

new and there is even an escalator to take pregnant women up to the

hondo. It was raining, the halls were closed and there was nothing much

to see. In any case, the eleven-faced Kannon is apparently displayed

only on the 18th of each month. I noticed one building with a phoenix

at each end of the roof, in imitation of the Phoenix Hall at Byodo-in.

Nearby was a urinal with an open door at each end, allowing the wind to

blow cherry-blossom petals inside and scatter them all over the floor.

And with that unique image in my mind I set off back to Kyoto and a hot

bath.

Matsunoodera (#29) November 2006.

I had decided to visit temples 28 and 29 on the same day as they are

both on Japan's west coast and not too far from each other. I

particularly wanted to get Matsunoodera out of the way first as it

sounded like it might be a hassle to get to. On the advice of Japanese

web sites I didn't intend to go all the way to the unmanned

Matsunoodera station and then walk to the temple because it would waste

a lot of time. Instead I took an express bound for Higashi Maizuru and

was told by the ticket inspector that the unreserved car I was sitting

in was going someplace else. I had to move to the first three cars

which all turned out to be reserved. It was only after some dodging

from seat to seat that I finally found one that didn't belong to

anyone.

Matsunoodera (#29) November 2006.